In a village in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, a woman receives a small but steady sum each month - not wages, for she has no formal job, but an unconditional cash transfer from the government.

Premila Bhalavi says the money covers medicines, vegetables and her son's school fees. The sum, 1,500 rupees ($16: £12), may be small, but its effect - predictable income, a sense of control and a taste of independence - is anything but.

Her story is increasingly common. Across India, 118 million adult women in 12 states now receive unconditional cash transfers from their governments, making India the site of one of the world's largest and least-studied social-policy experiments.

Long accustomed to subsidising grain, fuel and rural jobs, India has stumbled into something more radical: paying adult women simply because they keep households running, bear the burden of unpaid care and form an electorate too large to ignore.

Eligibility filters vary - age thresholds, income caps and exclusions for families with government employees, taxpayers or owners of cars or large plots of land.

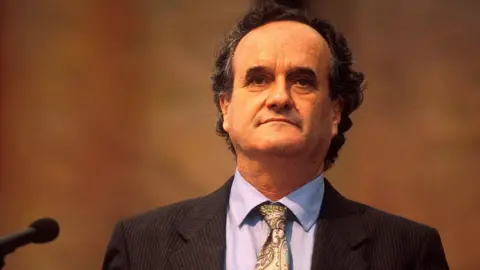

The unconditional cash transfers signal a significant expansion of Indian states' welfare regimes in favour of women, Prabha Kotiswaran, a professor of law and social justice at King's College London, told the BBC.

The transfers range from 1,000-2,500 rupees ($12-$30) a month - meagre sums, worth roughly 5-12% of household income, but regular. With 300 million women now holding bank accounts, transfers have become administratively simple.

Women typically spend the money on household and family needs - children's education, groceries, cooking gas, medical and emergency expenses, retiring small debts and occasional personal items like gold or small comforts.

What sets India apart from Mexico, Brazil or Indonesia - countries with large conditional cash-transfer schemes - is the absence of conditions: the money arrives whether or not a child attends school or a household falls below the poverty line.

Goa was the first state to launch an unconditional cash transfer scheme to women in 2013. The phenomenon picked up just before the pandemic in 2020, when north-eastern Assam rolled out a scheme for vulnerable women. Since then these transfers have turned into a political juggernaut.

The recent wave of unconditional cash transfers targets adult women, with some states acknowledging their unpaid domestic and care work. Tamil Nadu frames its payments as a rights grant while West Bengal's scheme similarly recognizes women's unpaid contributions.

In the recent elections in Bihar, the political power of cash transfers was on stark display. In the weeks before polling in the country's poorest state, the government transferred 10,000 rupees ($112; £85) to 7.5 million female bank accounts under a livelihood-generation scheme. Women voted in larger numbers than men, decisively shaping the outcome.

Critics called it blatant vote-buying, but the result was clear: women helped the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led coalition secure a landslide victory. Many believe this cash infusion was a reminder of how financial support can be used as political leverage.

Yet Bihar is only one piece of a much larger picture. Across India, unconditional cash transfers are reaching tens of millions of women on a regular basis.

Feminists argue that this represents a slow recognition of the economic value of unpaid domestic and care work. Cash transfers restore dignity to women who are otherwise financially dependent on their husbands for every minor expense.

Importantly, none of the surveys finds evidence that the money discourages women from seeking paid work or entrench gender roles - the two big feminist fears, according to a report by Prof Kotiswaran.

However, challenges remain to ensure that these cash transfers empower women consistently. The overarching aim must remain focused on creating sustainable employment opportunities alongside these policies, fostering true equity in society.