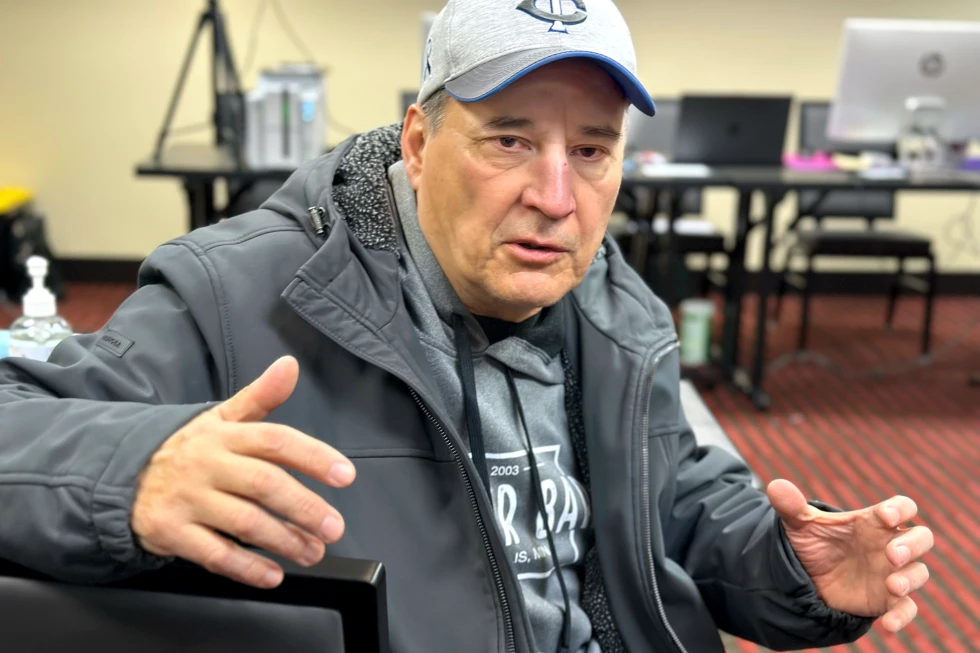

MINNEAPOLIS (AP) — Amidst the ongoing turmoil of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) activities in Minneapolis, Shane Mantz retrieved his Choctaw Nation citizenship card and placed it securely in his wallet. With a growing number of ICE raids, including one described as the largest immigration operation ever, Mantz fears being wrongly identified and apprehended due to his appearance.

Reflecting a wider trend, many Native Americans are now carrying tribal documents that serve as proof of their U.S. citizenship. This situation arises as the 575 federally recognized Native nations begin to ease the process of obtaining tribal IDs, including waiving fees, lowering eligibility ages, and accelerating issuance times, a response to the heightened fear of federal action.

This is the first time tribal IDs have been used widely as proof of citizenship and protection against federal law enforcement, explains David Wilkins, an authority on Native governance from the University of Richmond. His observations evoke a sense of frustration among Native communities, who feel unjustly persecuted.

As the first peoples of this land, there’s no reason why Native Americans should have their citizenship questioned, stated Jaqueline De León, a senior attorney with the Native American Rights Fund and member of Isleta Pueblo.

Since the late 19th century, the U.S. government has maintained detailed genealogical records affecting Native Americans' access to vital services. Generations have seen tribal nations issue their identification forms, and the last two decades have seen tribal photo IDs become integral for voting, employment verification, and travel.

With nearly 70% of Native Americans residing in urban areas today, many are actively engaging in initiatives to obtain their IDs, particularly in population centers like the Twin Cities. Events designed to assist tribal citizens have emerged, helping facilitate connections and resources. Christine Yellow Bird, director of a satellite office for the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, reports making numerous trips to Minneapolis to aid local citizens.

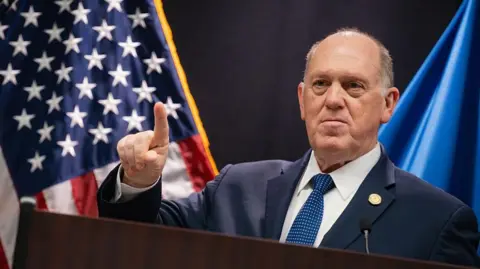

Reports of harassment by ICE highlight the severity of the situation. Last year, Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren noted that multiple tribal citizens faced detentions by ICE in Arizona and New Mexico, stressing the importance of carrying tribal IDs. Many stories reflect experiences of racial profiling and mistreatment, as exemplified by the harrowing encounter of Peter Yazzie, a Navajo man who was wrongfully arrested despite holding legitimate identification.

Mantz echoes the sentiments of many in the community when he questions, Why do we have to carry these documents? He emphasizes the internal conflict of pride in one’s identity while facing the uncomfortable necessity of proving it.

As the intensifying scrutiny from ICE looms over Native communities, the pressure to secure and maintain proof of identification is a significant and painful reminder of the complexities surrounding identity and citizenship for the original inhabitants of these lands.